When a municipality or a hauler wants to build a new materials recycling facility, it has to consider many aspects prior to construction. Before breaking ground, letting to bid, and even issuing Requests for Proposals (RFPs), many consult experts to help define their needs, as well as the potential of, and for, a material recovery facility (MRF).

Bob Rella and Deb Frye, senior vice presidents at HDR Engineering-national practice leaders for solid waste facilities, specializing in structural/civil and mechanical, respectively-have worked with many clients, providing oversight and helping develop projects. Their recommendations are independent of vendors, but, because of their experience in the industry, they are able to anticipate vendor input and modify based on the vendor selected.

First, says Frye, a site must be chosen. “We search for available property, taking into account the minimum number of acres needed,” she says.

Rella adds, “The site drives [the plan]. There may be unusable portions due to wetlands, for example. Each one is unique.”

Site Unseen

It’s important to understand the realities of the site, agrees Evan Williams, architect with Cambridge Companies. He mentions a project in Las Vegas where part of the property was in a flood zone. “We couldn’t do anything there,” he says.

It’s important to do a proper site assessment and know the site’s history. “You have to be aware of contamination issues, buried structures, and the impact on the surrounding properties,” explains Williams. “You don’t want groundwater issues, either.”

Pits for equipment can run 9 feet deep, with footings as deep as 11 feet. An area with a high water table could pose problems.

Access to highways, proximity to collection routes, and even the type of road material, which must be capable of handling heavy truck weights, are things to consider in site selection. Access to public transportation is also relevant because some employees may rely on it.

That same Nevada project encountered access issues due to high traffic on the main road, and because the site fronts onto an industrial street, a completely enclosable building had to be oriented to keep wind and sight lines away from the tip area. Best practices dictate that the doors are not visible from the road and the doors are oriented according to prevailing winds.

Remember to be a good neighbor by taking into consideration noise, odor, and traffic generated by the facility, and plan accordingly to reduce impact.

Marketability

While some consultants consider site selection to be the first step, others disagree. Jeff Eriks, chief business development officer for Cambridge, sometimes lays out the ideal plan before looking for property to suit. However, he admits, at times the site can dictate layout because it may drive heights. Some sites have height restrictions or may require special permitting.

Other consultants look at something else entirely. “Markets are the first thing to look at,” states Ernie Ruckert, client manager for Cornerstone Environmental Group LLC, a solid waste consulting firm. Determining markets dictates whether the end product will be loose, baled, or crushed-and that indicates the system design required.

The markets even determine the backend of the MRF. How many loading docks and how many types of materials will be produced indicates the amount of storage needed. Knowing what can be recycled, and what must be disposed of after processing, affects the design. Mixed-waste MRFs will need a different system and spatial plan than a single wastestream.

Once the markets are determined, Andrew Schellberg, client manager at Cornerstone, says they build around the equipment layout.

“You have to analyze the wastestream and the daily volume,” says Eriks. “How much glass, paper, and cardboard do you expect? How much residual is left to haul away or reprocess? Analyze the traffic by hour. How much storage or tip floor do you need at peak?”

In the Zone

Before work begins, a site analysis is performed. The first step of a site analysis is checking the state regulations, local ordinances, zoning, permitting requirements, and contract arrangements.

“There could be specific regulations or zoning requirements, depending on whether you’re dealing with industrial or solid waste, or whether the MRF is clean or dirty,” explains Rella.

Zoning regulations could dictate the minimum distance from the property line or the line of sight. Special environmental permitting may be an additional requirement. If the facility is going for LEED (Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design) certification, there will be additional guidelines and criteria specifically pertaining to energy efficiency.

Inside the building, other codes will apply. Emergency egress will need to be incorporated. Fire codes must be adhered to, and can determine where water nozzles are placed and how direct spray piping is designed.

Not Your Typical Drive-In

“Talk about traffic-where it will come from, where it will exit,” suggests Chris Hawn, North American sales manager for Machinex, manufacturer of equipment for recycling. Check local ordinances regarding the relationship to traffic. An old adage in the waste industry holds that it’s principally a transportation business, so trucks, traffic, and access must be considered in planning a MRF. “You need to understand traffic patterns,” emphasizes Hawn.

In the early 1980s, Machinex became the first company in Canada to design machinery for material recycling facilities.

Ingress/egress is often used as a guideline for siting criteria. Be cognizant of the site’s physical constraints: How many trucks can get in and out at once. Calculate the number of vehicles that will be maneuvering in and out. “How will you get the trucks in, weighed, dumped, re-weighed, and out?” asks Hawn.

Position the building properly. If it’s a small property, there won’t be enough room to do everything in front, Hawn says. “You may have to come in the front, get weighed, and drive to the back-get into the property to dump.”

The traffic entrance needs consideration, but accommodation must be made for a variety of vehicles. “You’ll need a citizen dropoff area for visitors,” explains Ruckert.

Schools often bus students in for outreach programs. Politicians also bring constituents in for demonstrations. “You’ve got to consider vehicle movement for material arrival, visitors, and employees,” states Schellberg. Parking for employees must also be provided.

Once a site has met the benchmarks, Rella screens, tests, and ranks the property with more sophisticated criteria. Next, the public gets involved, usually through a public comment period, especially if the developers have to change the zoning or if there are environmental concerns. Neighbors must be taken into consideration. A dirty MRF may raise apprehensions about odor, issues with garbage, or additional waste.

| Credit: BHS Designs Athens Services recently opened 80,000 ft2 MRF in Sun Valley, CA. |

Joint Effort

After a site has been chosen and approved, work can begin on a conceptual site plan that will take into consideration basic equipment layout, footprint, enclosure buildings, storage capacity, and traffic patterns.

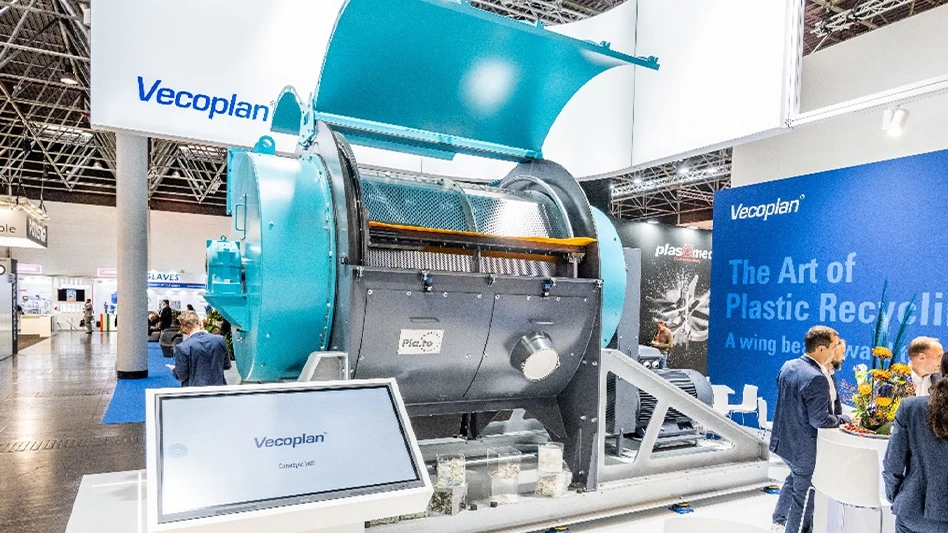

The facility is designed as an extension of the equipment, states Williams. “The equipment sets the functional and operational requirements, and the building plan responds to this to allow the equipment to operate as unencumbered as possible. The equipment footprint is determined by the equipment supplier and takes into account access for maintenance, material removal, and ideal operating conditions.”

In addition to the equipment, he lists other primary factors that influence the MRF building footprint: required tipping area storage, separated material bale storage, and employee support areas, which typically include locker rooms, lunchroom or break areas, a learning center for community meetings, and administrative offices.

If sorting lines are on an elevated level, Eriks likes to place the lockers on the same level and connect them with a platform. “You want all the sorters on one level,” he says. “It’s more efficient and safer; it’s better to exit on a platform and go straight to the sorting area. By keeping them off the concrete floor, they aren’t in the pathway of all the big yellow equipment driving around.”

He also advises putting the offices on the same level so managers can easily monitor productivity.

If constructing a new facility, it can be designed from the top-down, says Brian Wells, sales operation manager for Bulk Handling Systems LLC-an Oregon-based company that designs, builds, manufactures, and installs processing systems tailored to extract recyclables from the wastestream, and trains employees as part of a turnkey system.

“The building gets the first attention, but be sure to engage the architects early,” he says.

Wells advises collaboration in a parallel process. Historically, municipalities didn’t proceed collaboratively.

He says, “It used to be an individual process-sending out RFPs. A vendor sold equipment, but wasn’t an integral part of the project. Now the equipment is more advanced. It’s more common for vendors to be involved in the process, for the municipalities to look at it as a whole. It’s important to be done with everyone working together. When we work as a partner, we get the best results.”

Working with the civil planner and/or vendor can result in fewer compromises, and in the most efficient use of the building. “Private customers who are bidding call us,” continues Wells. “That enables them to predict the finances and the results better.”

Sizing It Up

The operation of the facility dominates the footprint requirements. Design the plant to accommodate everything and the kitchen sink, Wells jokes.

But there is some truth in his humor. The first question is universally considered to be: How many tons of material are collected per day? “How much material do you need to process?” continues Wells. “What is the material, and what do you want the end result to be?”

Start with current tons per day, Rella elaborates, and then look at your growth and make projections for the future. “Then it’s a business decision: do you want to incorporate that now, or build it later?”

If the budget allows, design it to be easily expandable for future growth. Eriks says that could encompass customer growth, municipal growth, or market growth. One of Cambridge’s projects in Jacksonville, FL, designed enough space for the later addition of a second line that would double their capacity.

“The goal is to have options,” he says. “You can save money by designing for expansion.”

In addition to how much material the building receives per day, Williams explains that the amount of tipping floor space needed is determined by how fast the equipment can process that material, and whether there are any surges of incoming material necessitating additional material stockpile areas. To minimize floor space, a taller push wall can be installed to allow material to be piled higher during peak times.

Beyond simply how many tons per day, “We need to know if it’s dirty single-stream, or curbside recycling, because it changes the design, the layout,” explains Frye.

There is a distinct different in the operation of both facilities. A dirty MRF is more labor-intensive: the picking percentage per person goes down, so more people are needed. A clean, single-stream MRF uses more equipment.

Design flexibility is important because what people throw away changes . . . and so do the markets. “Some municipalities get source-separated materials from other communities. They don’t want it to go through a single-source system,” says Rella. “We can design for multi-stream facilities, but it requires a larger footprint.”

With mixed waste, Wells says the major difference is the amount of organics in the stream. It averages 35% food and yard waste, which must be extracted due to concerns of contamination.

“A building must accommodate the segregating and processing of organics, and permit the trucks enough room to move the material,” says Wells. “You need more space, different equipment and odor control; a single-stream doesn’t worry about a scrubbing system for the air or a sprayer system.”

Stow Away

Information about the delivery schedule, daily volume, and processing posture-will the facility receive material during one shift, and process during two?-is part of the calculation needed to determine the size and footprint of a MRF.

“Trash doesn’t stop,” says Hawn. “You need to know the amount of tonnage that comes in every day, and you need enough space for a buffer of one to two days in case equipment goes down or something happens.”

According to Rella, some areas mandate three days of storage.

Again, it’s important to keep in mind what is being collected, because single-stream collection weighs less than mixed, so the buffer space required for two days is 1½ times bigger than for MSW.

Do you need onsite storage? Storage may be needed on the front and back end of the process. Eriks suggests at least a day-and-a-half for inbound and outbound storage, while Williams advises sizing the separated material bale storage area to hold several days of baled materials for off-loading onto semi-trailer trucks.

When a product is being generated, it may require inside storage to keep it from degrading. Cardboard is a good example of an end product that must be protected from the climate.

“You don’t want it to get rained on,” points out Rella. “You must keep it dry, or it degrades. Currently, the highest market material is fiber: OCC, cardboard. But if that market was down, some clients might hold on to their cardboard until the market got better. In those situations, the facility needs a bigger storage area.”

There might be other reasons for a large storage area. “You must know the shipment regulations for your area,” says Rella. “You may have to stockpile for a period of time while you’re waiting for a full truckload, so you need to know the regulations for stockpiling, such as keeping material under cover to control rain.”

Segregating materials for shipment, stockpiling containers and leaving room to maneuver between them affects the footprint. “You need to know what kinds of materials are recoverable,” states Frye.

Different source-separated materials have as high as 90-95% recovery, which results in baled commodities that could add to required site capacity. “A lot of clients struggle to balance spending with profitable material,” says Frye. “Recovery rates of clean streams are near 90%, which leaves 10% residue to be disposed of. The dirty side claims [percentages] in the 70s, but I’ve only seen 30 to 35%.”

Determining how to arrange storage can affect the site plan. Some material can be stored outside. There’s a variety of ways to store aluminum, for instance. It can be baled or shot directly into a container.

Tipping Point

Although Hawn says Machinex gets involved in building a MRF by interacting with the general contractor and customer for adequate tip floor space, he stipulates they don’t put up walls. Instead, they interact with the client by providing information about the loads/weight of the machinery, and how it’s dispersed across the floor to help determine flooring specifications.

“You have to take into consideration the static and dynamic loads of the equipment,” he says.

The heaviest pieces of equipment are the balers-and yet, it’s more often the tip floor that gets the most consideration. “Some pour a pad, some reinforce the area,” he adds.

The floor in a storage area is similar to that in an industrial warehouse, but of a higher grade. Most facilities establish more stringent criteria for the tip floor, though. Because it requires augmented strength, a mix design for high wear is suitable.

“You have to design the tip floor to receive and move material,” says Wells.

The type, thickness, and reinforcing is similar to what a transfer station uses, so he recommends using experienced consultants accustomed to designing for them.

Bill Butler, technology sales representative, Laticrete International Inc., outlines the basic scenario: garbage trucks dump their loads on the tip floor, and then a loader pushes the material into a recycling machine.

Laticrete offers several products to protect the tip floor from excessive wear due to impact, chemicals, or abrasion. “Wear starts with chemical attack from what’s coming out of the truck,” explains Butler. “It gnaws at the cement. Then, the loader further erodes the surface.”

Wear projections are based on tons per day. Butler estimates that 500 tons per day is average. “It’s all about intensity,” he says.

Based on those projections, he incorporates 20 years of experience to determine what will work best on that floor. Laticrete’s two main products are Duratop HP and Emery Top 400.

Most industrial facility floors consist of concrete that is 4,000 psi and prepared from regular, local aggregate. Emery aggregate is 12,000 psi, eight times more abrasion-resistant and lasts 10-12 years.

“It’s also lighter, so you get better coverage and save money,” points out Butler.

It may be lighter, but it’s rated the hardest material on earth on the Mohs hardness scale, except for industrial diamonds. Installed over concrete, it provides a double service life and internal sealing. “It’s less porous, so it doesn’t absorb liquid,” he says.

Whether building from scratch or rehabbing an existing facility, he recommends using Emery and Laticrete’s liquid chemical toppings, but, to save money, suggests applying them only put where the trucks dump.

Custom Design

Whether a facility is handling single-stream or MSW, it will have a similar layout: tip floor, processing equipment, bale storage on the opposite side. Beyond that basic arrangement, the design is based on the area.

Some MRFs will feature pits for the loading system. “They may want to penetrate the floor,” says Hawn, “because it makes it easier to push or scoop to load the feeder.”

A 10-foot-by-6-foot reinforced concrete pit enables the processing equipment to operate more efficiently. “They feed the conveyors after the material is separated,” he says.

In a green field, you want to build a home for the recovery equipment, but in older buildings that are retrofitted, ceiling heights may be pre-determined. Therefore, a pit provides more room to maneuver. “Pits are of consideration,” says Hawn.

When retrofitting an existing building that lacks space, if it’s possible to go up, it might be beneficial to do so. “You have the advantage of being able to drop things,” says Schellberg, “but it’s a tradeoff.”

Stacked equipment is more difficult to clean, maintain, and swap out. Maintenance may require a crane or a man-lift.

Maintenance considerations are part of a good design. “We look at the type of maintenance required, how often it’s needed and the number of hours a facility runs,” explains Ruckert. “Will maintenance be done on the weekend, during breaks or during a half-shift?”

Some equipment needs routine maintenance to create a consistent end product, so a layout should include easy access to the equipment. Many facilities use work platforms for safe and efficient access. “You need some space around the equipment,” says Ruckert. “There is benefit in including a couple extra feet for maintenance.”

Equipment layout and maintenance access drive the placement of other things, such as overhead lights Williams adds.

Another placement to consider involves wall penetration for the residue coming out of the plant, headed to the landfill.

“You need a hole in the wall at the right spot,” says Hawn.

Although BHS, founded in 1976, developed the first single-stream recycling system in the US, Wells says there are always new ways of processing. “It’s in the infancy of market growth and penetration,” he says.

Nevertheless, BHS, which manufactures sorting equipment designed to automatically separate commingled single-stream recyclables, is based on the importance of a one-pass operation. The company began focusing on turnkey recycling systems in 2005. BHS understands that systems must be robust.

Seasonal items can be problematic. For example, holiday lights can get caught up in the equipment.

“You must be prepared,” cautions Hawn. “You must maintain a very high focus on keeping equipment clean and running. The equipment must be built in a robust way, and so it’s easy to clean and maintain.”

Diligence must be practiced year-round, not just around the holidays.

“Garbage is brutal,” says Wells. “You’re moving material on conveyors; as it goes from clean to garbage, there’s more liquid, bulk, and corrosion.”

That conveyor arrangement can be affected by the shape of the building, Rella notes. That’s why he says if a client already has a building or a site they want to turn into a MRF, it takes a lot of talent.”

Engineering design requests sometimes call for new equipment in an old building. In th

Latest from Waste Today

- Worn Again Technologies unveils Accelerator plant to advance polycotton recycling

- Nashville Waste Services launches new digital route system

- ACUA landfill expansion project unanimously approved

- Clean Energy announces multiple RNG deals with fleets nationwide

- Interchange 360 to operate alternative collection program under Washington’s RRA

- Waste Pro files brief supporting pause of FMCSA CDL eligibility rule

- New Way Trucks expands US network with Joe Johnson Equipment

- Tire Industry Project publishes end-of-life tire management guide