When designing MRFs, there are a number of ways that design affects operations: single-stream versus multistream, tons processed per day, the number of sort streams, automated versus manual sorting, the amount of post-sort materials kept on hand awaiting transfer or shipment to recyclers, and the time at which an operation will be ready to go from one to two shifts.

Roland Zimmer, chief executive officer of Stadler America, says in designing a facility, “the better the design of the line is, the fewer personnel are needed.”

Cynthia Andela, engineer and president of Andela Products, says she has observed changes in MRF facility designs over the years.

The facility design affects operations in several ways, she points out.

First, does the facility design help the operators work efficiently?

“To accomplish this, the designer needs to consider the physical attributes of the sorting operators,” she says. “How far can the people reach? Is it better to throw over a belt or throw behind or next to the belt? Is there safe access to the platforms? Do they have clean air? Are the temperature variations not extremely hot or extremely cold?”

Second, does the designer understand the composition of the material that is being processed?

“Is the mechanical equipment in the design properly sized to handle the maximum load of material that is going to go through the system? Is the equipment accessible for ease of operations, but also safely guarded to prevent injury?” says Andela.

Third consideration: Are all of the machines accessible for ease of maintenance and repair?

“The equipment may operate efficiently when everything is running, but does it take a long time or require lots of heavy equipment to do maintenance?” says Andela, adding that downtime costs money.

Fourth consideration: Are the electrical controls clean and easy to operate?

“Does the system collect data at important points so maintenance can be scheduled before breakdown?” says Andela. “Data collection can help the operators refine the system for better operation.”

The facility is always a custom design depending on criteria such as single stream versus multiple streams, tons per day, number of sort streams, automated versus manual sorting, and amount of post sort materials kept on hand awaiting transfer or shipment to recyclers.

“To get a really good recycling system design, a fair amount of preparation work needs to be done,” Andela points out, adding an analysis of the material that will be coming into the MRF needs to be done to understand what is in the mix, both by volume and by weight.

“There needs to be enough space around the equipment to handle extra material that may pile up before processing, or processed recyclables ready to go to market,” says Andela. “Seasonal variations also need to be considered in how the mix of material will change and the weekly volume that will need to be processed.”

Additionally, the system design should provide as much flexibility as possible with diverters, movable conveyors or other options that will allow the operators to make adjustments as unforeseen changes occur in the type of material that comes in the door, she adds.

“One example of this is the great increase in shredded paper with the introduction of home shredding system,” says Andela. “This means that shredded paper falls through the screens and is mixed with the containers and with the broken glass. To recover this paper as a recyclable commodity, technology is available to remove the shred with density separation or air separation.”

Andela’s crusher and pulverizer technology is designed to provide a selective reduction technology along with an air separation system to remove the glass from the shredded paper, the plastic caps, small metal and other debris.

“It is often difficult to find room at the MRF for more equipment that is needed due to the change in the material composition,” says Andela. “If the original system design allows for expansion, then additional technologies can be added at a later time as needed. But many times, new MRFs are wedged into older, existing spaces and there is not enough room for storing material that comes in for finished material storage or to allow for access to the equipment for maintenance or design changes.”

Andela says the decision to go from one shift to two shifts is determined by the labor force and the economics of paying more overtime or finding people to staff and work a second shift.

The design and layout of the equipment has a major impact on if a MRF can be well operated, says Brian Schellati, director of business development for Van Dyk Recycling Solutions.

“The selection of poor equipment and/or a complicated layout can doom a facility no matter how skilled the operator is,” he says. “With that said, a very well thought out layout with premium equipment can still be poorly maintained and operated.”

Schellati says the factors that affect facility design in order of importance are building footprint and layout; budget; amount and type of material processed with tip floor space required; automated versus manual sorting, with manual sorting taking up more space; working hours per day, including number of shifts; product storage-bales-required; and local restrictions, such as no processing or material outside the building, or limited working hours due to noise ordinances.

While there are many factors that influence when to go from one to two shifts, “it usually comes down to how many tons per hour a MRF can process,” says Schellati. “Financially, it is best to design a plant to run as many hours per day as possible in order to maximize the return on investment but the downside of this is usually lack of expansion and limited maintenance time.”

The design of the MRF facility directly impacts operations in a number of ways, says Randy Baerg, president of Warren & Baerg Manufacturing.

“There are a few simple things that, if not considered, cause large problems,” he says.

One is incoming and outgoing traffic.

“Will the public be bringing in any materials to the facility, such as recyclables, greenwaste, other wastes?” Baerg points out.

Another consideration: traffic flow patterns so that the MRF is out of the way of plant operations.

One factor to consider is whether the facility is being designed for a specific type of waste flow.

“It is important to know and test the waste flow as best as possible so that the equipment and lines in the facility are designed to handle the percentages of different materials,” Baerg says. “If the equipment is designed to handle a specific material stream and the figures were off or not checked, then when those materials do not show in the flow the facility has useless equipment and no revenue flow from that material.”

Other factors that affect facility design include tons per day received, hours of receiving material, hours of plant operation, single-stream versus multistream, what materials and how many types will be sorted for recycling, what materials will be sent to landfill, whether sorting will be manual or automated or both, whether the facility will divert any of the sorted materials to a line to produce an alternative fuel from the nonrecyclables, and whether there will be foodwaste or greenwaste.

Generally, if the facility has to have nearly double the equipment to handle the flow in one shift, it is best to go to two shifts and reduce the equipment required, says Baerg, adding that some facilities are located where there are restrictions on the allowed hours of operation, which can affect the equipment required.

“We aren’t in the waste business; we are in the reliability business,” says Steven M. Viny, the chief executive officer of Envision Holdings, which encompasses Envision Waste Services, Envision Realty Group, miniMRF, and Columbia Technologies in Cleveland, OH.

“Rubbish and recycling service knows no holiday,” he adds. “Our customers demand that the materials placed on the curb be picked up without fail. The same applies to the processing of mixed waste for the recovery of recyclables-dirty MRF-or to single-stream or multistream processing facilities. Murphy suggests that everything mechanical will eventually fail. After 20 years of designing and operating MRFs, I tend to agree with Murphy.”

As such, the equipment and the building need to be mindfully designed for preventative maintenance and catastrophic maintenance as well as equipment replacement, Viny points out.

“I have seen large equipment in the middle of the facility. The large components were placed first during construction. Should that piece of equipment need to be completely replaced 10 years later, there is no way to reach it with a crane without disassembling many other pieces of equipment,” he says. “This contributes to significant downtime.”

Some pieces of equipment, such as bales, can be built with two motors and two hydraulic pumps rather than one larger one, Viny says.

“Often, such balers can continue to operate on just one of its hydraulic systems, albeit at a lower productivity rate,” he says. “This redundancy offers the flexibility to operate and finish the day before maintenance is performed. Often modern equipment can include optional controls that monitor operating hours and can advise the operator of maintenance schedules that must be performed.”

Even wheel loaders and skid-steer loads can be equipped with “trash packages” designed to protect radiators, windscreens, wheel bearings, and tires, among other factors, Viny says.

“The bottom line: rubbish is a very difficult environment for equipment,” he says. “While designing for appropriate maintenance will cost more initially for both the building and equipment, it will pay huge dividends in the long run.”

There is an inverse relationship to MRF capacity and its ability to withstand downtime, says Viny.

“The greater the daily capacity, the less the facility can cope with length downtime,” he adds. “One of the biggest factors affecting facility design is the competitive bidding process as well as those reviewing the bid responses. In many cases, all emphasis is based on the bid price.”

That means that the MRF developer has to weigh the extra costs associated with proper design for maintenance along with keeping the costs low so as to win the bid, says Viny.

“This is a delicate balance,” he adds. “The same is true for building size as it relates to materials storage. The more storage space in the building, the larger the building envelope and, as such, the higher the overall price.”

At the same time, those reviewing the bids often do not have the in-house technical skills to evaluate MRF equipment and building design to determine if enough attention was given to maintenance, Viny says.

“Every MRF requires maintenance, be it an older hand-sort line or a fully automated system,” he says. “Clearly as automation increases, so does maintenance. Moisture also is an important factor in plant maintenance. Wet waste and recyclables tend to move more slowly, screen less efficiently, and carry more grit along than dry waste or recyclables. Areas with high moisture will see increased maintenance requirements.”

Envision Waste Services has designed and operated dirty MRFs since 1993.

“Since that time, we have never lost a single day of processing, ever,” says Viny. “That kind of record does not happen by accident. Maintenance is a discipline that starts on the drafting table and must be continued each day in the plant operation.”

There are multiple considerations for running a two-shift operation versus a one-shift operation and as such, that determination needs to be made on a case-by-case basis, says Viny.

As explained by Chris Hawn, North American sales manager for Machinex, there is an unprecedented trend towards dirty MRFs.

“As much of this trend is based upon emerging technologies,” Hawn points out, “it’s important to ensure that the MRF or preprocessing facility is based on a sustainable business model. Such issues as wrapping of shafts, jamming of equipment, and complete loss of efficiency through equipment blinding should be of primary importance when considering the design of a system.

“We view each project as having its own identity and, therefore, the need for a custom design to meet the requirements of the particular application,” Hawn maintains. “The design process must be subject to a careful evaluation of the mass balance of the system.”

National Recovery Technologies supplies optical sorting equipment that detects various materials specifically for the MRF and works with its parent company, Bulk Handling Systems, to design complete MRF systems.

“These facilities are becoming more sophisticated and as recovery rates are going up worldwide, the performance of optical sorters becomes increasingly important,” says Matthias Erdmannsdoerfer, company president. “Not only when you think about recovery and purity rates of materials that are being sorted but also in terms of lifetime customer support of these systems and maintenance costs going forward.”

Of note is the “green fence” in China, where contaminated shipments are being rejected.

“The big complaint is the quality of the material that is shipped to China in terms of the paper quality and the contamination of these shipments going to China. For any MRF operator, the higher quality is PET bales. For these MRF operators, it’s all about return on investment, so the equipment performance and the design of these systems play a very important role.”

Erdmannsdoerfer says the flexibility-as well as performance-of a system over time plays a critical role as the material composition is bound to change.

“By the time the MRF actually gets started, the material stream has changed already from whatever you designed it for,” he adds.

With optical sorting equipment, the high-priced items are PET, HDPE and mixed plastics, Erdmannsdoerfer says. “Recovery is number one and number two is purity of their bales,” he says. “That’s what the buyers of these materials are looking for.”

Erdmannsdoerfer says significant developments on the recovery side and the function of the optical equipment have significantly changed the industry.

“If you look back four to six years, you’ll find hardly any optical machines in the MRFs,” he says. “Now MRFs are becoming more complex, meaning more valuables are being removed from the screen by optics.

“It used to be just PET and then PET and HDPEs…and now PET, HDPEs and mixed plastics, fiber, film. The complexity is constantly increasing, and we as an optical supplier are pushing the envelope constantly to increase the value stream in these MRFs.”

When designing a material MRF, there are numerous factors that must be considered, weighed, and analyzed throughout the concept design process. Some of these factors include inbound material composition, building dimensions, throughput requirements, budget constraints, end product specifications, and specific operating requirements, notes Dirk Kantak, director of sales for CP Manufacturing.

“Throughout the design process, we work closely with our customers to customize the system design to meet both their throughput and performance requirements,” Kantak says.

Each facility receives a different mix of inbound materials, which is called the material composition.

“The inbound material composition guides us in the development of the overall layout design, including the individual equipment required to successfully separate the inbound materials into a marketable end product,” says Kantak.

Factoring the inbound material, throughput, and separation performance requirements, each system is designed to maximize its processing efficiencies.

“Material recovery facilities provide a valuable service to the local community in terms of landfill diversion, but we are also mindful that each system must be designed to be as economically viable as possible,” Kantak notes.

Labor is another variable involved with system design.

“Manual sorting is another factor that we consider in the development of a MRF design. The human element is invaluable in removing certain types of material that cannot be removed via mechanical or optical separating equipment,” says Kantak.

Another consideration in designing a MRF is its geographic location.

“Local weather plays a role in the level of the moisture content of the inbound material stream, so we are always conscious of the geographical location of the facility and we design the system to meet those conditions,” Kantak notes.

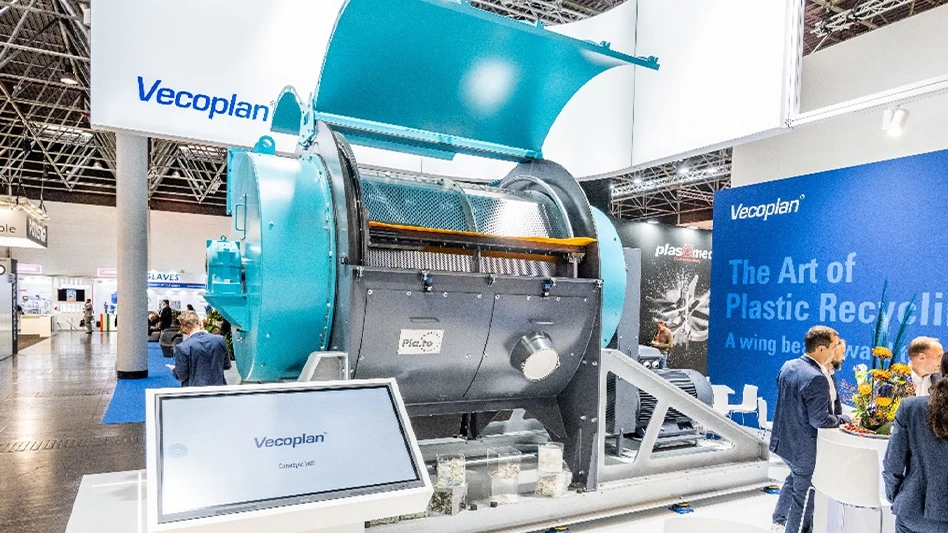

| Equipment design and its layout have a major impact on MRF operations. |

Jim Miller of JRMA, an engineering and technological firm, has been engaged in solid waste facility design of MRFs and transfer stations for nearly 30 years, as well as anaerobic digester facilities of late.

He also is a guest at UCLA on solid waste facility design, with a segment on MRF designs.

“A MRF is a number of things, one being the equipment system,” says Miller. “The equipment system has specific places where it has to be loaded-the infeeds-and it has specific places where it discharges recovered materials or residue.

“Recovered materials are baled or in the case of glass and a number of other materials, deposited into bins and taken off. Reject/residual materials are discharged somewhere and have to be removed for disposal, so the overall MRF layout has to allow for that,” he adds. “The most effective MRF design provides sufficient space at the right locations, so it accommodates the necessary material and vehicle movements and maximizes the efficiency of the equipment.”

Equipment layout should always be the driver of a MRF design, says Miller.

“Unfortunately, sometimes MRF operations have to work with existing buildings and do the best they can,” he points out. “When you’re starting from scratch on a greenfield project, the best idea is to try to work out the MRF layout first and work all of these other needs around it.”

“Starting at the beginning, the more different types of materials you process or the more different collection streams you bring in, the more staging area is needed,” says Miller. “For instance if you’re processing residential single stream, clean commercial, and mixed commercial, each of those is collected separately and brought to the facility separately. There must be enough space for tipping and staging each of those different streams, determined by the volume of each stream.”

The various tipping and staging areas must be arranged based on the layout of the equipment, particularly where the materials are fed into the system, says Miller.

“If the plant is working two shifts and the material may be collected during the day or during the night in some cases and may come in within an eight- or 10-hour window. If so, and you’re processing over a 16- or 20-hour window, you have to provide enough floor space to stage the surge of material volume until you can process it.”

The equipment footprint is dictated by the number and type of the unit processes taking place at the MRF-the different streams being processed and the variety of operations and sorting functions, Miller says.

“Typical residential source-separated streams have only containers and fibers and relatively little contamination. Sorting systems for that type of stream may target only aluminum, tin, two grades of plastic, newsprint, and cardboard. Other streams may have three colors of glass, mixed paper and multiple grades of plastic,” he says. “Multifamily streams may have the same basic composition, but much of the waste stream will be in plastic bags, requiring a bag opener for effective sorting.”

These are a few examples of how variations in waste streams require different processing and dictate how many devices have to be in a MRF, Miller says.

“Once the unit processes and devices are determined, an arrangement worked out. The more processing, the more equipment and the bigger the footprint unless you can go vertical and stack various operations, which is pretty common these days,” he points out.

The next consideration is that of the space requirements for recovered and residual materials.

“A baling operation has its own space needs, its own in-feed conveyor,” says Miller. “You have to be able to get the material to that conveyor. Usually, that’s done automatically, but it still takes up space. The baler itself takes up space and has to discharge the baled goods. You have to have sufficient room for the bales to be discharged and room for the forklifts to get the material and take it to where it’s going to be stacked or shipped.”

Space is needed for materials that aren’t baled, such as glass. Those are generally discharged into bins and room is needed for those bins as well for the vehicles that maneuver the bins in and out of the building, Miller adds.

If the MRF is a standalone one with no transfer station attached to it, there needs to be some means for transferring the residual materials out of the building, typically to a landfill.

“Residue may be consolidated utilizing a compactor or possibly dumped onto the floor or into a bunker and loaded into a vehicle with a loader,” says Miller. “Either way, there’s a certain amount of space requirements for that, including maneuvering space for vehicles.”

What’s left is the room for storing baled goods, which has a lot to do with the markets and how large the M

Latest from Waste Today

- Worn Again Technologies unveils Accelerator plant to advance polycotton recycling

- Nashville Waste Services launches new digital route system

- ACUA landfill expansion project unanimously approved

- Clean Energy announces multiple RNG deals with fleets nationwide

- Interchange 360 to operate alternative collection program under Washington’s RRA

- Waste Pro files brief supporting pause of FMCSA CDL eligibility rule

- New Way Trucks expands US network with Joe Johnson Equipment

- Tire Industry Project publishes end-of-life tire management guide