As waste composition changes with the times and as labor shortages continue and political considerations ebb and flow, efficiencies in and between the transfer station and materials recovery facility (MRF) become more critical.

“MRFs that are not coordinated with transfer stations are unlikely to produce the best benefit/cost to the owner/operator and would not have the highest efficiency,” notes Bruce J. Clark, P.E., project director, SCS Engineers.

The best approach, says Clark, is one in which a “high tech” municipal solid waste MRF would refer to a facility that uses a high degree of automation as opposed to more manual labor for various waste separation tasks including conveyors and other automated separation equipment throughout the facility.

The MRF equipment and the overall system is designed around the major wastestreams and flow of waste expected from the transfer stations and other sources, if appropriate, and the expected material recovery rates, Clark says.

“Each major wastestream has to be broken down to its various fractions, whether organics, commercial, and residential, including if there are single-stream flows, and each one addressed with a process designed to optimize recovery and meet the recovery goal,” he adds.

Evan Williams, project designer for Cambridge Companies, notes that most solid waste operators are not only eyeing the MSW/transfer station market, but also recycling.

Williams cites a few “overarching” trends that have been on the radar for a decade or longer.

“On the MSW side, increased diversion is a reality for governing authorities in many areas,” he says. “It’s being adopted somewhat evenly across the industry.”

Landfills in some areas accept the vast majority of material whereas in other areas, there are specifics as to what materials are not allowed in landfills or there is a percentage goal, Williams says.

There also is the “dirty” MRF in which all of the materials are taken to the transfer station and sent to the MRF for sorting.

Cambridge Companies helps waste operations determine the appropriate facility size, efficient site layout, and what functions it will serve.

Other factors considered include hours of operation, type of customers and incoming material, daily tonnage, loading equipment, recycling requirements, landfill hours, and round-trip distance from the landfill.

Market trends are showing an increase in recycling and a decrease in materials going to the landfill, says Jeff Eriks, vice president of business development for Cambridge Companies.

“The total volume of material will not necessarily decrease—just more of it will be going to sorting facilities,” he adds. “When you’re looking at the intersection between the two from the standpoint of the transfer station, the impacts would be to make your facility more flexible so you would have the ability to either store two materials on the floor without contaminating the single-stream recyclables, or you need the ability to coordinate the trucking to be sending it to different facilities.”

Managing the flow of material is one of the biggest challenges for solid waste operators, Eriks points out.

“You can have a properly-sized facility for your volume, but if all of your volume comes in a one-hour time span, you can’t handle it,” he says. “The important thing is the coordination between the volume creators and the volume processors. A transfer station is sending materials to a MRF and they absolutely need to be coordinating those semis. There’s a big difference between a route truck that’s dumping a load and a semi that’s bringing in a walking-floor load.”

While technology such as route optimization can, to a certain extent, come into play, “ideally, the MRF should be coordinating with vendors when the material is coming in and how much is coming in. These are estimates and over time it’s variable, but you need to set those parameters up front or else you’re operating blind.”

A best management practice, when practical, is to implement RFID at transfer stations and MRFs to save time and queuing, notes Williams.

“When you have vendors you work with all of the time, one of the more time-consuming portions of operating a transfer station or a MRF is checking in the people at the scale house and weighing the load. They go in and unload and you weigh them on the way out and give them their ticket,” he says.

The use of available technology at transfer stations and MRFs frees up employees to tend to other matters, notes Williams.

“They’re able to perhaps more carefully monitor the screens that are viewing what’s on the tipping floor to make sure everyone is operating in a safe manner rather than constantly having to be putting out weight tickets for trucks,” he says.

Generally speaking, a MRF that sorts the recycling bin from a house sorts all that it can sort and then sends it direct to mill or to a secondary processor, notes Mike Centers, president of Titus MRF Services.

“If a MRF has trash, it sends it directly to a transfer station or directly to a landfill—more the latter,” he adds.

But as the MRF evolves, it is acting as a transfer station, “given (in many cases) the amount of trash or material that at this time is not sorted by material type, has to go to a landfill, and exceeds 10% of the incoming—so a MRF is a transfer station,” says Centers.

“What is developing in California is a secondary MRF that cleans what the first MRF chooses not to sort or misses as the MRF’s yield loss,” he adds. “That secondary MRF has a different design to clean up this material.”

He cites as an example a secondary processor for glass—Strategic Materials—which takes glass from a MRF, cleans it, and then sends it directly to mill.

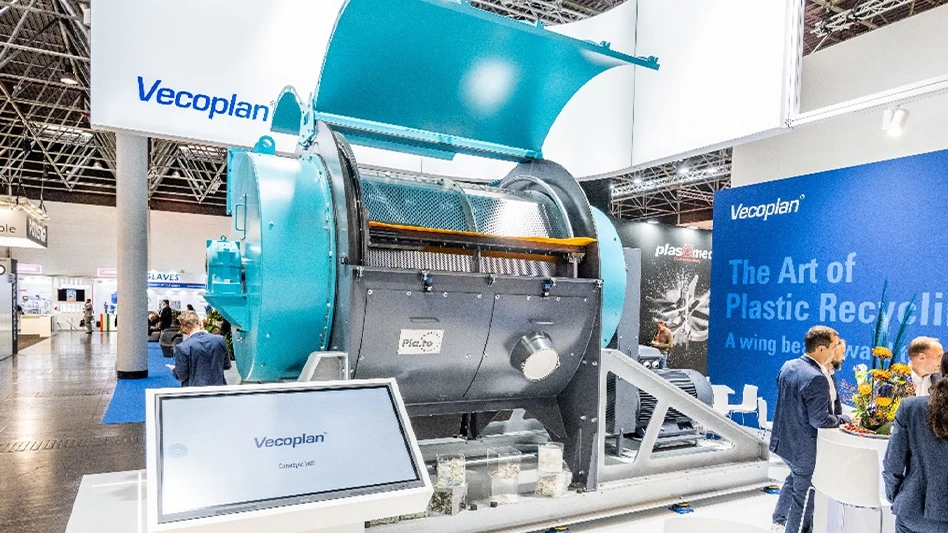

Scott Jable, director of North American sales for Stadler, is noting more queries as to what parts of a MRF operation can be automated.

“The China and quality issues notwithstanding, one of the main issues driving MRFs to become more technologically advanced is the inability to get labor,” says Jable. “They’re trying to reduce labor and increase capacity, but especially increase quality. That’s hard to do if you don’t have the automation.”

Optical sorting and robotics is the focus of the greatest demand, says Jable.

And it’s not identifying the material that’s the primary issue, but rather the mechanical acquisition of it, says Jable.

Another primary concern is finding ways to mitigate the problem of plastic film wrapping around the axles of star screens or disk screens, Jable notes.

Many manufacturers have made improvements in their screens to reduce the amount of wrapping and the time it takes to clean them every shift, he says.

Stadler utilizes the trommel and ballistic separator concept that is designed to resist wrapping incidents and reduce the need for pre-sorters, says Jable. He notes that the type of retrofits in which MSW operators are expressing interest focuses on including ballistic separators and optical sorters.

One area that sometimes doesn’t get the attention it needs but is critical to efficient and safe MRF and transfer station operations is the floor.

In spending money on facilities and equipment, it’s equally important to consider the floor, says Jim Andrews, president of American Restore.

“The concrete is not a place you want to skimp,” he adds.

MRFs are fed in a variety of ways, Andrews points out.

“Facilities that don’t do a lot of volume can sometimes surgically load them with excavators or small machines where they fill up the hoppers,” he says. “The operations doing big volumes are feeding walking floors or conveyors in a tipping environment. So they’re pushing the materials around on a concrete or walking floor or conveyor that feeds the MRF.

“The problem we’re seeing all over the country is they’re not paying attention to the wear, where that concrete meets the steel embed of the floor and protects and provides the integrity of the walking floor conveyor.“

Consequently, it can get to a point where that steel has been caught up in a bucket or machine or something in the wastestream between the bucket and the floor that starts to rip the steel out.

A condition assessment enables the solid waste facility operator to set up a timeline on the need for repairs or replacements based on daily tonnage. It allows time to monetize the work, Andrews points out.

In a MRF, the predominant disaster is where the equipment catches the steel edge of a conveyor or walking floor and impugns it to the point where the mechanics don’t work and the walking floor stops and can’t be used, Andrews points out.

Jeff Bonkiewicz, channel manager for Laticrete, points out that MRFs and waste transfer station floors are typically 3,500 to 4,000 psi concrete that is eventually worn down by leachates that “eat away” at the floor as well as front loaders that push a lot of the waste across the waste transfer station in a way that causes abrasion.

“This happens multiple times a day, every day,” says Bonkiewicz. “Typically, these can be 24/7 facilities but at the very least six days a week. The abrasion can go all the way down to the rebar or the dirt and make for very unsafe flooring for these facilities and cause safety problems for their employees.”

Transfer station operators have two options, says Bonkiewicz.

“They can clean up as best as they can, shut down, and put down regular concrete again,” he says. “That’s an inexpensive option, but it will require them to be down for a longer period of time. The other option is they can go with a floor hardener topping in the construction chemical product class.”

For the solid waste industry transfer station tipping floor, Laticrete offers EmeryTop 400, designed for environments where there is constant abrasion impact as well as chemicals that destroy the cement paste holding the aggregate in place.

It can be placed over existing concrete floors or freshly-installed concrete. The average thickness of placement is between 3/4 of an inch and 1 inch or more if necessary.

EmeryTop 400 has a Mohs hardness of 9 for greater abrasion resistance. It is designed with high energy-absorbing capacity for improved impact resistance, non-rusting, increased resistance to chloride ion penetration, and a modulus of elasticity similar to concrete.

“Everybody is looking for a place to take their mixed fiber material and some people are storing it, so even if China opens its doors, it’s going to be a few months until things normalize, whatever the new normal is,” notes Jable.

“There’s going to be a lot of material out there that’s available and that will initially be available at cheaper prices. It’s going to come down to where if things don’t change drastically, then the bottom-line is we’re all going to have to start paying for our recyclables just like we pay for landfilling our trash if we want to do something good for the environment.

Latest from Waste Today

- Worn Again Technologies unveils Accelerator plant to advance polycotton recycling

- Nashville Waste Services launches new digital route system

- ACUA landfill expansion project unanimously approved

- Clean Energy announces multiple RNG deals with fleets nationwide

- Interchange 360 to operate alternative collection program under Washington’s RRA

- Waste Pro files brief supporting pause of FMCSA CDL eligibility rule

- New Way Trucks expands US network with Joe Johnson Equipment

- Tire Industry Project publishes end-of-life tire management guide