The vast majority of landfill emissions, perhaps 99%, consist of two relatively simple compounds: carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4). The other 1% may include hydrogen sulfide (H2S) along with an impressive list of non-methane organic compounds (NMOCs), inorganics, and occasionally metals.

You’ll notice that both CO2 and CH4 contain carbon, a little atom that is receiving a lot of press lately. Think “carbon footprint;” think “carbon sequestration;” just think “greenhouse gas (GHG).”

CO2 is perhaps the most frequently cited GHG, and other GHGs are often expressed in terms of their CO2 equivalent. For example, methane is also a GHG and has, pound for pound, approximately 30 times more impact than carbon dioxide. Consequently, methane is the primary focus when it comes to controlling landfill emissions.

To gain perspective regarding these two compounds, you should know that it’s not as though the planet is drowning in carbon dioxide and methane. According to NASA, CO2represents only 412 ppm in the atmosphere (as of 2019). Expressed as a ratio in air, this means there is 1 part CO2 for every 2,427 parts of something else.

But methane is even less concentrated than CO2, with an atmospheric concentration of 1,800 ppb, or about 1 in 555,556. I’m tempted to say that atmospheric methane is about as rare as 4-leaf clovers, but Wikipedia cites a survey that determined the occurrence of 4-leaf clovers is 1 in just 5,000.

But rarity is not the point. Rather, it’s that these two compounds have been identified as significant GHGs, and because landfills are what might be considered a point source, there is a push to control those landfill emissions.

In the big picture, there are many other sources of methane and CO2, some natural, some man-made.

Methane Generation

Methane sources are commonly split into two categories: naturally occurring and human-related.

According to an EPA estimate from 2017, “Municipal solid waste (MSW) landfills are the third-largest source of human-related methane emissions in the United States, accounting for approximately 14.1 percent of these emissions in 2017.” But if you read this carefully, you’ll find the term, “human-related.” That means that it doesn’t include natural sources of methane, which are also significant, because worldwide GHGs originate from many sources. In terms of human-related methane production, landfills rank below what’s generated from the fossil fuel industry (the biggest contributor)—and digestive emissions from livestock—mostly cows.

Carbon Dioxide Generation

Carbon dioxide emissions are also split into man-made and naturally occurring sources. Fossil fuel burning, mostly from coal used for power generation, dominates the man-made list.

Let’s get back to the landfill perspective. When an alternative fuel such as CNG is derived from landfill gas, traditional production leakage isn’t a factor. CNG produced from landfill gas is also used to help close the loop on carbon emissions because it has become more widely used on garbage trucks. Fact is, while the waste industry—and specifically landfills—is often ignored and even looked down upon as being somewhat less than environmentally-minded, there are some stellar examples to the contrary.

When most people in our industry think greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, our thoughts automatically go toward how we can control emissions from thousands of landfills or tens of thousands of garbage trucks. These are important questions and they represent an opportunity for us to show off our good work.

Could we do more? Yes, but before we get into that discussion, I’d like to put a few things into perspective. Like many of you, I have had plenty of opportunities to participate in seminars, workshops, public meetings, and a host of other events where we discussed issues related to GHG emissions. And too often, the overall theme follows an assumption that the waste industry in general, and landfills specifically, are drowning the planet in methane and carbon dioxide. This assumption is unfair and patently untrue.

Hopefully, you have not been sold this bill of goods. The fact is, the waste business is far down the list of GHG producers, and at the top of the list of industries working to minimize emissions. I am also convinced that we have an excellent opportunity to control much of the GHG that is generated at landfills. With the EPA’s estimate that 14% of methane in the US comes from landfill emissions, they have also identified a very concentrated collection of 4-leaf clovers…and a definite target at which to apply our effort.

But if this concept is difficult for you to grasp, or if you're you having a hard time dealing with feelings of guilt for being in the waste industry, I think I can help.

Quick: make a list of industries that commonly utilize fleets that have been converted from diesel to natural gas. For most people, this is a pretty short list. It won't include long-haul trucking, or local delivery trucks, or dump trucks, or concrete trucks, or low-beds, or school buses, or …much of anything else. But you can bet that garbage trucks will be on the list, and probably at the top. Yes, many city buses have been converted to natural gas, but if we look at industries that also include lots of private operations that are doing something to reduce GHG emissions, we'll come back to the garbage business every time.

The perspective is good. It helps us prioritize our goals and balance our effort. Along that line, here is some perspective about where landfills fit into the overall GHG picture.

Controlling Landfill Emissions

Due to the greater impact that methane has as a GHG, it receives more attention and is the primary target when it comes to controlling landfill emissions.

Methane (CH4) is the simplest of the alkanes, a family of flammable gasses that are made with the simple atomic building blocks of only carbon and hydrogen. It’s a familiar list that includes such things as Ethane, Propane, Butane, Octane, and a few other flammable gases.

At this point, it appears that all landfills have been lumped, like a busload of rowdy schoolboys, into a single category of GHG emitters. Consequently, our industry is on its way toward controlling landfill emissions by diverting the organic portion of the wastestream that goes into landfills.

But here’s the rub: While I agree with the science that says, “If we remove organics from the landfill wastestream, they won’t be generating gas,” I don’t—in every case—agree with the logic. I love a good idea as much as anyone else but believe we need to also think about the cost. No matter how many times you shuffle those cards, it always comes down to the money.

Shutting off the flow of organics into a landfill is not quite the same as turning off a light switch. Unlike electrons that will stop immediately, the buried waste that is currently generating GHG will keep right on doing it, likely for many decades, regardless of what we do with tomorrow’s organics. Sorry brother, but that train has already left the station.

That means that existing landfills will still need to install and/or continue to maintain their LFG extraction system, even as we force the creation of another family of expenses. I’m talking about the new collections, sorting, composting, digesting, and other processing that will be required when we split off the organics from the rest of the wastestream.

From a business perspective, we'll be forced to continue spending money on LFG extraction systems, even while we're forced to spend money on new organics-processing systems. Does anybody see an issue here?

Seems to me that the waste industry is already struggling with too many recycling programs that have been mandated, but which were not financially sustainable. Let’s be careful we don’t run this weasel around the mulberry bush again.

Certainly, there are good reasons for diverting some or all organics away from some landfills—in some situations. But what we don’t want is to upset one apple cart while trying to fill another.

What if individual landfills had the flexibility to determine their destiny, based on the volume of waste in place, the effectiveness of their LFG collection system, and objective financial analysis? In my world, we call this Value Engineering.

In some instances, it could make sense to separate those organics. But in other cases, it may make more sense to use the landfill—and the landfill’s existing LFG-processing facility—as an LFG Generator. It already is one.

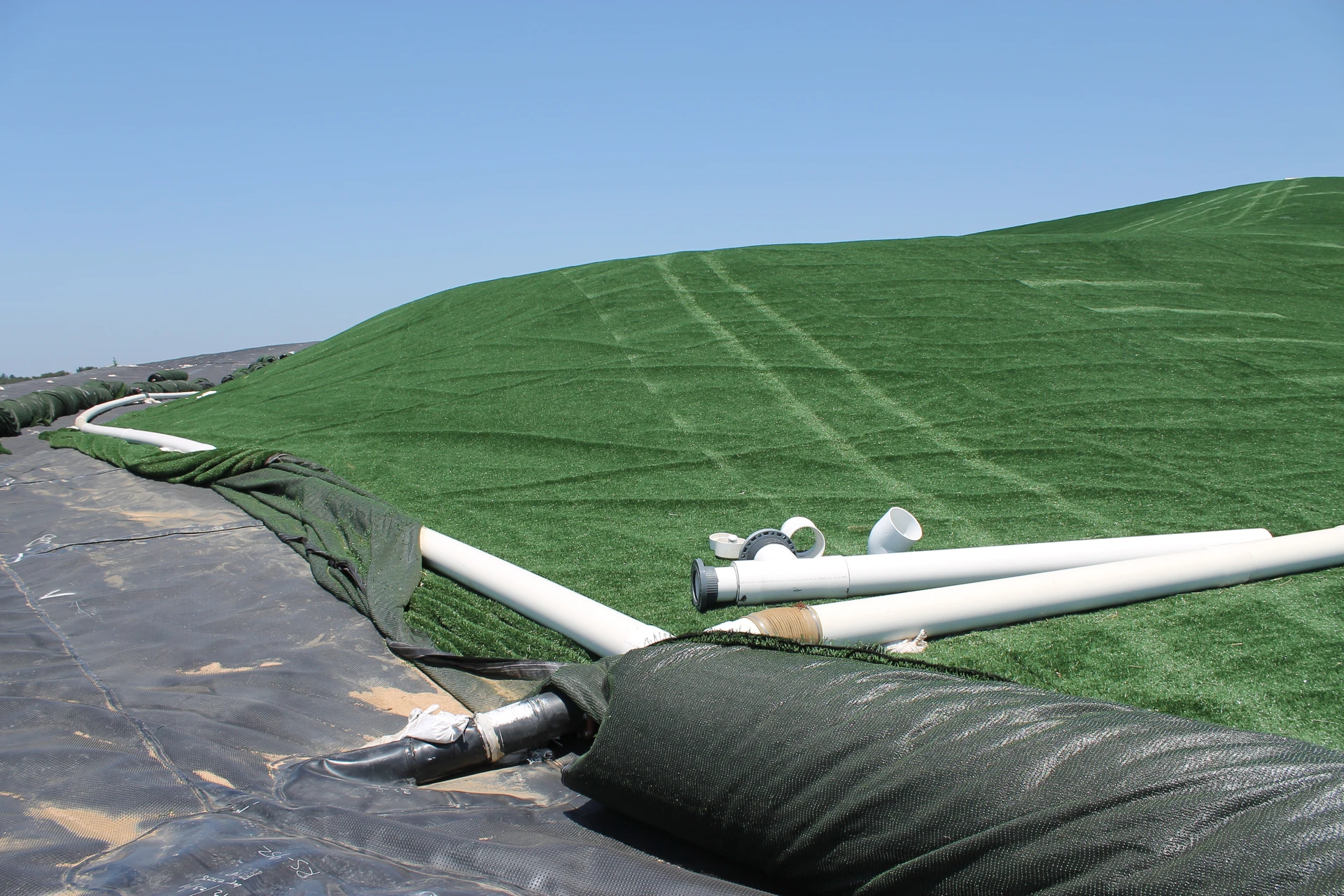

I’m talking about enhancing the LFG collection systems at selected landfills (where it makes sense) so that they are more effective at containing and extracting LFG. I think this is a valid concept that is at least worth some discussion. I have been involved with several landfills that developed very robust cover systems. Cover systems that could—in conjunction with an effective bottom liner—do an excellent job of retaining methane.

According to the EPA’s Landfill Methane Outreach Program (LMOP), there are currently 578 LFG projects operating at landfills in the US, and another 480 sites that are good candidates for extracting methane as an energy resource.

The Landfill “Gas Generator” Option

As previously noted, one of the most obvious ways for reducing gas emissions is to limit the amount of organic material going into landfills. Easy Peasy. But some folks in the waste industry have tossed a dissenting question on the table: Why spend all that money to modify collection systems and create alternative facilities for extracting energy from organics when landfills are so effective at generating methane? “Would it,” they ask, “not make more sense to just enhance the methane retention and recovery rate at landfills?”

This reminds me of a quote by the late Peter Drucker: “That there is nothing so useless as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all.”

Using landfills as primary energy generators to create clean power and control GHG will sound counterintuitive to many. Like the idea of putting cow manure on your backyard garden to help grow big, juicy organic tomatoes. For some folks, the idea that a landfill could have any beneficial use is just…wrong.

Operational Steps for Reducing Emissions

Okay, we’re at a point where we acknowledge that landfills generate a significant percentage of man-made methane and also some carbon dioxide. Regardless of what we decide to do with organics in the future, all existing landfills will continue to produce landfill gas. The logical question is then: What can landfills do to minimize emissions? There is a two-tiered answer, one for the landfills that do not have an LFG collection system and another for those that do.

All landfills will generate and emit landfill gas at a rate that’s directly related to the amount of waste in place and moisture within that waste mass. At most landfills, the organic fraction within the landfill will eventually break down from solid to gas, but the moisture content of that waste is the dominating factor in terms of how fast that will occur.

Certainly, the quantity, type, and concentration of organics within the landfill is a factor, as is the age, depth, and density of the waste. But all other things being equal, it is moisture that sets the pace in terms of how quickly decomposition occurs. Generally speaking, the landfills that are producing the highest rates of LFG are wet landfills.

No LFG System

For starters, landfills with no LFG collection system should consider installing one. Notice I suggest they should consider installing a system. There is a financial and practical limit—a sort of minimum threshold below which a system doesn’t make sense.

There is, of course, more to the “consider” equation.

What are your goals? If you are simply trying to prevent subsurface migration, then a passive system may be all you need to relieve the internal pressure that’s pushing LFG laterally beyond the landfill boundary. Just know that a passive system will not reduce GHG emissions.

Alternatively, do you want to also minimize GHG emissions? If so, you’ll need an active system that includes some form of combustion or fuel refinement. Simply venting that gas doesn’t work, you’ve got to burn it.

Over the years I’ve seen some funny things, such as small landfills that were too small and generated too little methane to run even a flare efficiently and consistently—so they purchased propane to supplement methane…just to keep the flare burning. Yes, this process did allow those low-producing landfills to burn off methane, but would such an approach stand up to a life cycle analysis that considered the methane releases that come from additional gas drilling, production, and processing?

Then there’s the money. Regardless of your gas-control goals, you’ll need to find a way to pay for it. In many cases, grants may provide the incentive and financial foundation for installing a system. In that cost/benefit analysis, some landfills will generate enough revenue to justify the cost of installing a system, but many others will not.

There is also another very serious consideration—long-term revenue. On one hand, LFG collection systems depend on the long tail of production to provide many years of ongoing revenue that’s required to amortize the cost of design and construction. Unfortunately, if the organics are removed from the wastestream, that long tail will become flatter and shorter.

Active LFG System

For landfills with an active LFG extraction system, some of those same financial issues must be considered. Again, the financial models that initially justified those systems were dependent on long-term generation.

But further, those existing systems should be evaluated to determine the cost/benefit of encapsulating the waste mass to more effectively contain the gas.

What would it be worth to your LFG collection system if you could increase the quantity of LFG you contain and utilize another 20, 30, or 40%? I’m guessing it would be worth plenty. Taken a step further, how would the additional cost of doing that compare with the cost of creating an entirely new operating system to extract and process organics?

Landfill emissions are an issue, and we must find ways to reduce them. But I also believe that there may be—in some cases—a better solution than just closing the valve on organics. The challenge we face is not based on an unwillingness to work hard or be creative. We have plenty of muscle and brainpower. No, our challenge is one of perspective. Until we accept the idea that landfills are—and could continue to be—an important and integral part of the waste industry, we run the risk of missing a potentially good opportunity.

My grandfather taught me many valuable lessons, and he also grew some of the best tomatoes in the county, with vines sometimes reaching a height of 6 feet. He did it by…well, I think you know.

Latest from Waste Today

- My Green Michigan expands depackaging capacity

- Washington selects Circular Action Alliance as PRO

- Ten-8 Industrial opens new central Florida service center

- Triumvirate Environmental acquires Environmental Waste Minimization

- Official NYC Bin availability expands ahead of deadline

- US Food Waste Pact’s 2025 Impact Report shows decrease in food waste

- Coastal Waste & Recycling expands recycling operations with Machinex

- Reconomy acquires German-based GfAW