Recycling stands poised to become the dominant operating factor of the solid waste management industry. Except for major efforts during wartime emergencies (like the scrap metal and scrap rubber drives of World War II), recycling for most of the past century was limited to the ever-volatile scrap metal market, local community programs, charitable fund raising, and public relations efforts. According to available data (see the EPA’s Municipal Solid Waste Generation, Recycling, and Disposal in the United States: Facts and Figures for 2006), recycling rates as measured as a percent of total municipal solid waste generated annually held steady or only increased slightly from 1960 to 1980. For those two decades, recycling increased from only 6.4% to 9.6%, never exceeding more than one-tenth of the wastestream. However, starting in 1985, recycling programs started to take off and cut into ever-increasing portions of the solid waste market. By 1990, recycling rates jumped to over 16% and then went on to account for over one-fourth of the waste management market by 1995. As of 2006 (the latest data available), America recycled almost one-third of its municipal solid waste, a fivefold increase in less than half a century.

The raw numbers are equally impressive. Again starting in 1960, only 5.6 million tons of wastes were recycled out of an available 88.1 million tons of waste generated that year. Annual recycling quantities did not head north of 10 million tons until two decades later when America recycled 14.5 million tons. Since then, the annual amount of waste recycled in the US has almost reached 82 million tons out of an available 251 million tons. This represents an average increase of over 2.5 million tons each year, and is equivalent to an annualized growth rate of approximately 7% that has been sustained for over a quarter of a century. Since 1970, by comparison, American GDP growth has averaged 3.16% per year, after inflation. Largely as a result of recycling and the flattening of per capita waste disposal rates, the amount of waste being sent to landfills for final disposal peaked in 1988 and has been slowly declining ever since (see Characterization of Municipal Solid Waste in the United States, US Environmental Protection Agency, updated 1996).

So what gets recycled? Items that are easily separable or are not normally considered part of the typical municipal solid wastestream (such as automobile batteries and tires) are the most obvious candidates for recycling. In addition, batteries and tires are mandated by law from being disposed of in landfills, the first because of its corrosive pollutants, and the second because of the fire hazard it represents. Similar to these first two are yard trimmings, which like batteries and tires are typically part of the standard waste set out on the curb for pickup each week. Again, many states have yardwaste bans designed to minimize the amount of landfill space taken up by this material. Recycled yardwaste gets diverted to local or regional composting operations. Of the remaining wastestream, materials with the greatest market demand get recycled the most. This includes steel food cans, paper and cardboard. This leaves the least recycled items, various types of plastic and glass.

Can these numbers go even higher, or have we reached to practical limits of our recycling efforts? Traditional multiple-stream recycling, with its emphasis on enthusiastic voluntary homeowner participation and labor-intensive processing techniques, may have “hit the wall.” But a relatively new approach, single-stream recycling, takes a capital-intensive approach and applies mechanical and technological advances to the art and science of material separation and recycling. It has the potential to achieve even higher levels of recycling. However, this approach requires new plant and equipment, and can often represent a significant capital investment. The question then gets transformed from “Can we recycle more?” to “Should we recycle more?” and “Is it worth the effort and cost to transition to a single stream recycling approach?”

So Why Recycle?

Before we can start to answer the question of whether or not we should recycle more by examining why we recycle in the first place. Simply put, recycling reduces the amount of resources wasted by throwing away garbage. However, resources are also expended by this effort. These expended resources can include time spent by homeowners sorting newspapers from milk and capital outlays to purchase and install shredding and sorting equipment. The more important question is whether or not the net resources saved (available recycled waste materials less the effort and materials needed to recycle them in the first place) represent a cost-effective approach.

The net savings can be measured in terms of direct market value and opportunity cost avoidance. There has always been some sort of market for recycled materials. Historically, this has been primarily the scrap metal market. Typically, these markets have been notoriously volatile with unpredictable market swings in the prices paid for scrap metal and other recyclables. For example, the average national price of scrap steel on the scrap metal market varied from $250 to $400 per ton during the past year. But something new has been added to the equation. While still very volatile, scrap metal prices have been trending upward with the increasing demand for steel, copper, and other industrial metals by emerging economies, most notably China and India. Indeed, the value of copper has increased so rapidly that a black market has emerged with criminals stripping old (and sometimes new) homes for their copper piping and copper wiring. They have even been known to risk electrocution to strip copper wire from fully operational electrical power substations. China, India, and the rest of the rapidly industrializing world still have a long way to go before they achieve Western-living standards and economic stature. In the meantime, their hunger for all manner of recycled materials, from crushed concrete aggregate to tin cans, remains voracious.

So, recycling isn’t an example of busybody regulators imposing their wills on a reluctant public and business community. The recent growth in recycling, is to a large extent, demand driven. If recycling didn’t exist, this demand would create it—government interference or not. Not that the government would have to force recycling down people’s throats. For the most part, recycling is popular with the public and profitable for industry. Neither view recycling as a terrible burden.

Opportunity cost avoidance also factors into the equation. These opportunity costs start with the tipping fee at the local landfill. For example, a scrap metal recycler may be disappointed in a recent low price for his steel on the scrap metal market. But in addition to that sales price, he is also avoiding tipping fees at a landfill that would otherwise receive his metal. The typical nationwide tipping fee of around $30 per ton should be considered an automatic cost savings to the mangers, collectors, and haulers for waste that is recycled instead, no matter what the current market value is for the materials.

And finally, not everything of value is measured in dollars and cents. Whether it is due to the traditional American Puritan ethos of “waste not, want not,” which believes that wasting good materials is somehow sinful, or the modern New Age environmentalist movement’s dedication to protecting and saving the planet, and preserving it for the future, people receive important psychic benefits from participating in recycling efforts.

Traditional Multistream Recycling Operations

Multistream collection relies on the sources of waste (homeowners, businesses, industries) to separate the various recyclable materials. These are usually sorted manually into different bins and usually referred to as “source separation.” Not every kind of waste has to be separated individually. While certain wastes (food and plastic for example) cannot be placed in the same sorting bin, other wastes (such as plastics, aluminum, and glass) can be combined. Still, the result is a series of individualized waste streams of unique or similar waste types that arrive at the recycling center.

Manual presorting of the waste makes the job of the recycling center easier, but puts the burden of the program on the sources of the waste. By its very nature, multistream recycling is labor intensive and low tech. However, the labor in this case is “free” in the sense that the homeowners and office workers doing the sorting are not directly paid for their efforts. Since the suppliers separate out their own recyclables, the effort required by the final processors is greatly minimized. Drivers pick up the bins of preseparated waste and check for possible contaminants as they load the recyclables into segregated compartments on the trucks. This is, in effect, a second manual stage of waste sorting combined with transport. This presorting makes the job of the final sorters much easier and can greatly minimize or completely remove the need for processing equipment.

However, multistream recycling won’t work without the enthusiastic participation of homeowners and businesses. Unless the presorting is kept fairly simple, or until such time as more complicated separation tasks become routine habits, a multistream recycling program has to be rigidly enforced. In fact, certain European countries force participation in their multistream recycling programs by use of extreme methods such as spy cameras, trash spies, and heavy fines for failure to participate or properly separate recyclables. All these enforcement mechanisms translate into increased overhead costs that would be absent from a less demanding program.

As such, many multistream recycling programs (especially here in the US) are less ambitious. In effect, they can be classified as dual-stream recycling systems that require homeowners to separate out only easily managed materials, such as newsprint in one bin and bottles and cans (of all types) in another. Instead of emphasizing individualized bins for every conceivable category of recyclable waste and attempting to achieve very high percentages of recycling, these compromise programs go for the “low hanging fruit”: waste items that are easy to sort out yet represent a significant portion of the wastestream. They try to maximize results, while minimizing efforts instead of trying to achieve an ideal recycling goal.

The processing facility that accepts recyclables from a multistream program is referred to as a “materials recovery facility” (MRF), or, more specifically, a “clean” MRF. There are several different types of clean MRFs, but the most common handles the dual-stream program described above.

The first stream consists of a mixed assortment of food and beverage containers (glass, metal, PET, and HDPE plastics), and the second stream consists of mixed paper (mostly newsprint, brown paper, and glossy magazines).

No process is 100% efficient, and even the best-designed, clean MRF, operating as part of a popular multistream program, will have a rejection rate where unrecyclable materials are sent to a landfill. This rejection rate can vary from 3% to 20%. Staffing varies with the quantity and type of wastes being recycled and can range from 15 to 85 people.

Clean MRFs have several advantages including a relatively high processing efficiency and high quality of recycled materials (though these results are very dependant on the presorting that occurs before the waste arrives at the MRF). They rely on proven, simple designs and can provide work opportunities for the disadvantaged and unemployed. However, this labor force has to be protected from dust emissions, potential disease vectors, and a fire risk from storage accumulated materials onsite.

Setting Up a Single-Stream Recycling System

Single-stream recycling sets the above logic on its head by substituting high-tech equipment for voluntary sorting. It uses only one bin (or trash can) to collect all of the various types of recyclables. These mixed loads of waste are hauled directly to the processing facility as a single stream of waste without any presorting by homeowners or businesses. The sorting is done at the processing facility almost exclusively. In contrast to the clean MRF used in multistream recycling, single stream recycling is processed at a facility referred to as a “dirty” MRF. Dirty MRFs rely more on mechanical sorting, as well as manual handling of the waste, to create clean, segregated recyclables for sale on the scrap market. These materials serve as high-quality feedstock for reuse in the manufacturing of new products.

There are several potential drawbacks to multistream recycling and dirty MRFs. First, dirty MRFs tend to have higher rejection rates than those of clean MRFs, recycling only 45% or less of the incoming waste. However, this is not exactly an apple-to-apples comparison since almost the entire waste stream goes through a dirty MRF, not just preselected items already sorted for final processing. Furthermore, since the waste is commingled, that rate of cross contamination of the incoming waste stream is higher. This results in greater processing costs (costs that cannot be hidden by forcing homeowners to separate their waste without being paid for the effort). The responsibility for sorting out recyclables is almost entirely on the shoulders of the processor.

The one great advantage enjoyed by single-stream recycling programs is that they are user friendly. Homeowners and businesses are not faced with the task of separating out individual types of waste for pick up and processing. As such, participation rates increase with the adoption of a single-stream recycling program as does the popularity of the program. Public participation is rarely an issue of concern. Aesthetics and litter control improve with the reduction of the number of receiving bins and canisters. The overall convenience of the system and its reduced labor costs are its chief selling points.

However, a dirty MRF represents a significant capital cost investment in the processing and sorting equipment needed to run the operation. This equipment includes the following:

Magnetic separators—These remove ferrous metals from the wastestream by means of attraction generated by an electromagnet. The most popular configuration is a belt-magnet separator, where a moving belt carries the wastestream either under or over an electromagnet. Either the belt itself is magnetized, or there are magnets installed directly under the moving belt. As the belt turns under the last roller and begins its return cycle, nonferrous waste drops off the end of the belt into a collection bin. Meanwhile, the ferrous metal continues to stick to the belt until it is carried to a blade that scrapes it loose so it can fall into its own receptacle.

Eddy-current separators—These remove nonferrous metals (mostly aluminum cans and foil) by using magnetic fields generated by rapidly spinning magnetic rotors with alternating polarity to induce an electric current in these metals. These electrical currents in turn create their own magnetic fields, which in this case have opposite polarities to the spinning rotors. As a result, the nonferrous metals are repelled from the rotors and are propelled into nearby collection bins.

Disc screens—These are one of the types of separators that handle nonmetallic waste. They are designed to remove large but lightweight objects (such as cardboard boxes) from heavier but smaller objects. Once metal waste has been removed by magnetic belts and eddy current separators, the rest of the waste is fed via a variable-speed conveyor belt to an inflow bin. The bin provides a surge capacity to regulate inflow into the disc screener. The screener consists of a floor lined with rotating discs of varying dimensions, diameters, and shapes (ovals, stars, or circles) operating at different speeds. They are arranged in rows and decks configures so that the large and lighter objects are carried to the top of the waste flow as if carried up on a wave. There, they can be removed from the wastestream.

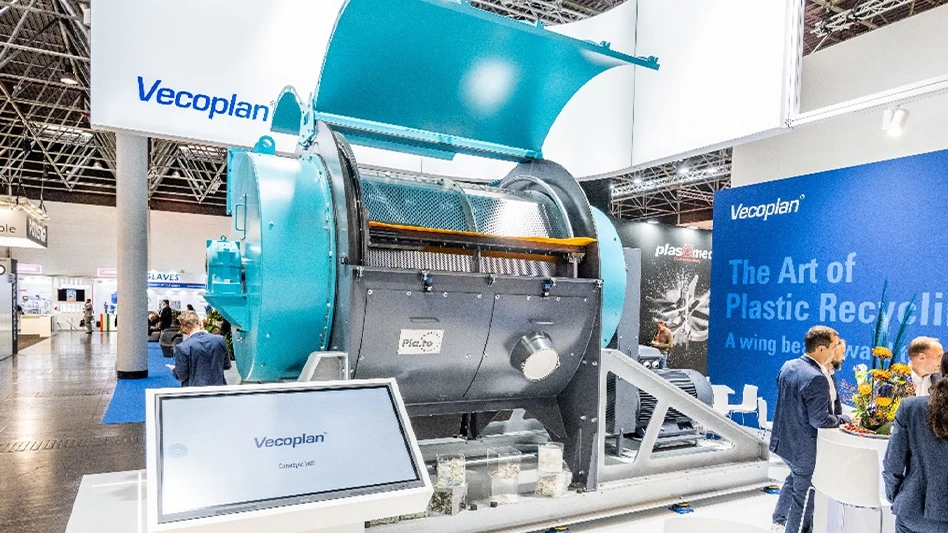

Rotating trommels—These originated as mining equipment designed to remove slag from valuable ore and have been modified to manage highly variable wastestreams. Essentially a large, rotating metal canister with perforations on its side, the trommel allows unrecyclable fines (soil, grit, glass shards, yardwaste, and other reside) to fall out of the perforations. A series of parallel vanes set in the interior walls of the canister retain and separate large objects suitable for recycling. The axis of the rotating trommel is usually set at an angle to allow for easy gravity feed, the angle varies with the amount of waste being processed and the speed of the inflow.

Air classifiers—These also got their start in the mining industry and have been adapted to recycling. An air separator clarifies incoming waste by weight. Configured as a large chimney, a high-pressure airflow sucks the waste up the stack with waste being fed into the midpoint of the stack. Heavy objects fall to the bottom of the stack for collection and further separation. Lighter objects are carried up to the top of the stack where they enter a cyclone separator. The cyclone further separates the waste by size and density.

Air knives—These consist of high-pressure air blasts arranged in sheets of air flows operating in parallel as the waste passes under them. By separating the airflows, swirling and unwanted remixing of the waste is prevented. This allows for finer separation of materials whose mass and density vary only slightly (various grades of paper such as newsprint, glossy magazine stock, or office paper)

Glass color separators—This leaves the last method of sorting, a method based on the colors of the objects being sorted. Once metals have been separated magnetically and electrically, after paper and related products have been separated by size and weight, there remains glass and plastic whose primary difference is color. This technique utilizes light spectrophotometry, which is effective for distinguishing between different colors of glass (clear, amber, brown, green, and ceramic cullet). The different colors’ wavelengths are reflected to an optical sensor. A more advanced optical sensor, the near infrared (NIR) sensor can also differentiate between plastics of varying densities as well as varying colors of glass. Combined with air blowers, the system can determine which type of plastic or glass is being read by the sensor and a puff or air can push it into an appropriate receptacle.

In addition to the above capital equipment and related costs, there are other set up costs associated with a single-stream recycling system. These include replacing multiple or dual collection bins and receptacles with new carts and the acquisition of new collection vehicles.

The building housing the dirty MRF equipment has to be constructed, and usually on another location than the existing clean MRF, since a dirty MRF usually has a larger footprint and floor space requirements. A new education and public announcement program will be required to inform the public and the business community how to participate in the new recycling program. Processing costs may increase (due to capital costs and the inability to hide labor costs with unpaid homeowners), and sales prices may decrease if the process produces poorer quality recyclables.

Public interest groups may have a vested interest in multistream recycling and may oppose the introduction of a single stream program. Residents adjacent to the proposed location of a dirty MRF may have similar objections.

Greater convenience and efficiency usually wins out over these objections. As a result, single-stream recycling is gaining popularity across the US and has even been making inroads in Europe. Yet, it would be simplistic to say that one method is inherently superior to the other. Both have their place, with their applicability determined by a variety of economic and demographic factors. Each community can choose the method that is right for them.

Latest from Waste Today

- Worn Again Technologies unveils Accelerator plant to advance polycotton recycling

- Nashville Waste Services launches new digital route system

- ACUA landfill expansion project unanimously approved

- Clean Energy announces multiple RNG deals with fleets nationwide

- Interchange 360 to operate alternative collection program under Washington’s RRA

- Waste Pro files brief supporting pause of FMCSA CDL eligibility rule

- New Way Trucks expands US network with Joe Johnson Equipment

- Tire Industry Project publishes end-of-life tire management guide